Other chapels were progressively created around the interior periphery of the building over the following centuries, many of them funerary chapels built through private patronage. Notably, during the early period of the cathedral-mosque, the workers charged with maintaining the building (which had suffered from disrepair in previous years) were local Muslims (Mudéjars). The area of the mosque's mihrab and maqsura, along the south wall, was converted into the Chapel of San Pedro and was reportedly where the host was stored. Soon after this date both the middle dome of the maqsura and the wall surfaces around the mihrab were covered in rich Byzantine-influenced gold mosaics. More famously, a rectangular maqsura area around the mosque's new mihrab was distinguished by a set of unique interlacing multifoil arches. According to Susana Calvo Capilla, a specialist on the history of the mosque–cathedral, although remains of multiple church-like buildings have been located on the territory of the mosque–cathedral complex, no clear archaeological evidence has been found of where either the church of St. Vincent or the first mosque were located on the site, and the latter may have been a newly constructed building.

The space under this dome was surrounded on three sides by elaborate screens of interlacing polylobed arches, similar to those of the maqsura to the south but even more intricate. The ribs of this dome have a different configuration than those of the domes in front of the mihrab. The tensions that grow from these subverted expectations create an intellectual dialogue between building and viewer that will characterize the evolving design of the Great Mosque of Cordoba for over two hundred years. It served as a central prayer hall for personal devotion, for the five daily Muslim prayers and the special Friday prayers accompanied by a sermon. The Christian-era additions (after 1236) included many small chapels throughout the building and various relatively cosmetic changes.

The Mosque-Cathedral of Cordoba (World Heritage Site since 1984) is arguably the most significant monument in the whole of the western Moslem World and one of the most amazing buildings in the world in its own right. Nowadays, some of the constructive elements of the Visigoth building are integrated in the first part of Abderraman I. In this same place, and during the Visigoth occupation, another building was constructed, the “San Vicente” Basilic. Some 850 pillars divide this interior into 19 north-to-south and 29 east-to-west aisles, with each row of pillars supporting a tier of open horseshoe arches upon which a third and similar tier is superimposed. Passing through the courtyard, one enters on the south a deep sanctuary whose roof is supported by a forest of pillars made of porphyry, jasper, and many-coloured marbles. The ground plan of the completed building forms a vast rectangle measuring 590 by 425 feet (180 by 130 metres), or little less than St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

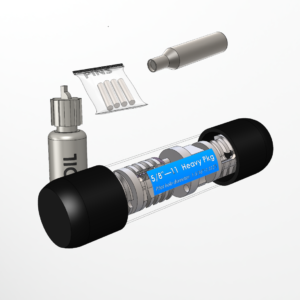

Extra naves

An inscription is also included in the mosaics of the middle dome of the maqsura, in front of the mihrab. More inscriptions are carved into the stone imposts on either side of the mihrab niche's arch, above the small engaged columns. The three bays of the maqsura area (the space in front of the mihrab and the spaces in front of the two side doors) are each covered by ornate ribbed domes. The lower walls on either side of the mihrab are panelled with marble carved with intricate arabesque vegetal motifs, while the spandrels above the arch are likewise filled with carved arabesques. The mihrab opens in the wall at the middle of this maqsura, while two doors flank it on either side. The dome is now part of the Villaviciosa Chapel and two of the three intersecting arch screens are still present (the western one has disappeared and been replaced by the 15th-century Gothic nave added to the chapel).

These three areas appear to have been the most important focal points of Christian activity in the early cathedral. It is likely that the mosque's minbar was also restored at this time, since it is known to have survived long afterwards up to the 16th century. As a result of both this pillage and the earlier pillage during the fitna, the mosque had lost almost all of its valuable furnishings. Indeed, the collapse of authority had immediate negative consequences for the mosque, which was looted and damaged during the fitna (civil conflict) that followed the caliphate's fall (roughly between 1009 and 1030). After the collapse of the Umayyad Caliphate in Cordoba at the beginning of the 11th century, no further expansions to the mosque were carried out.

List of chapels

- The space under this dome was surrounded on three sides by elaborate screens of interlacing polylobed arches, similar to those of the maqsura to the south but even more intricate.

- This wall-less cathedral looks as though it was just plopped into the middle of the mosque – a truly strange sight to behold.

- In 1816 the original mihrab of the mosque was uncovered from behind the former altar of the old Chapel of San Pedro.

- Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba, Islamic mosque in Córdoba, Spain, which was converted into a Christian cathedral in the 13th century.

- Over the centuries, Cordoba’s Mosque-Cathedral has been a testing ground for building techniques which have influenced both the Arabic and Christian cultures alike.

- The first major addition to the building under Christian patrons is the Royal Chapel (Capilla Real), located directly behind the west wall of the Villaviciosa Chapel.

An archaeological exhibit in the mosque–cathedral of Cordoba today displays fragments of a Late Roman or Visigothic building, emphasizing an originally Christian nature of the complex. This attractive building in Cordoba was built by order of Philip… As a result, the interior resembles a labyrinth of beautiful columns with double arcades and horseshoe arches. It was built in 785 by the Muslim emir Abdurrahman I, on the site of the ancient Visigoth church of San Vicente.

- It was probably instituted not only to make use of Mudéjar expertise but also to make up for the cathedral chapter’s relative poverty, especially vis-à-vis the monumental task of repairing and maintaining such a large building.

- The rectangular area within this, in front of the mihrab, was covered by three more decorative ribbed domes.

- The design was drafted by Hernan Ruiz I, the first architect in charge of the project, and was continued after his death by Hernan Ruiz II (his son) and then by Juan de Ochoa.

- The Puerta de las Palmas (Door of the Palms) is the grand ceremonial gate from the Courtyard of the Oranges to the cathedral’s interior, built on what was originally a uniform façade of open arches leading to the former mosque’s prayer hall.

- Further restoration works concentrating on the former mosque structure were carried out between 1879 and 1923 under the direction of Velázquez Bosco, who among other things dismantled the baroque elements that had been added to the Villaviciosa Chapel and uncovered the earlier structures there.

The Capilla Mayor and cruciform cathedral core

A unique building with a history spanning eight centuries. The deep emotional responses that the mosque evoked in him found expression in his poem called "The Mosque of Cordoba". Al-Idrisi, writing in the Almohad era, devoted almost his entire entry on Córdoba, several pages in all, to describing the great mosque, giving almost forensic detail about its constituent parts. The diocese never presented a formal title of ownership nor did provide a judicial sentence sanctioning the usurpation on the basis of a long-lasting occupation, with the sole legal argument being that of the building's "consecration" after 1236, as a cross-shaped symbol of ash was reportedly drawn on the floor at the time. The building was formally registered for the first time by the Córdoba's Cathedral Cabildo in 2006 on the basis of the article 206 of the Ley Hipotecaria from 1946 (whose constitutionality has been questioned).

Bell tower and former minaret

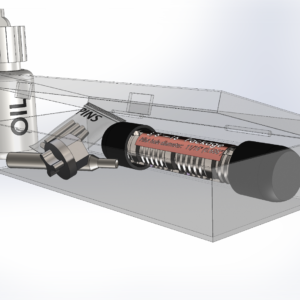

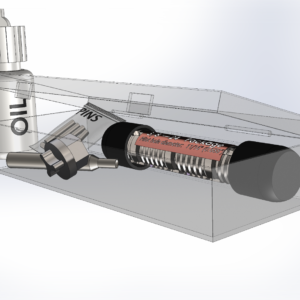

Construction of a new cathedral bell tower to encase the old minaret began in 1593 and, after some delays, was finished in 1617. Nuha N. N. Khoury, a scholar of Islamic architecture, has interpreted this collection of inscriptions in al-Hakam II's expansion of the building as an attempt to present the mosque as a "universal Islamic shrine", similar to the mosques of Mecca and Medina, and to portray Caliph al-Hakam II as the instrument through which God built this shrine. In the nave or aisle of the hypostyle hall which leads to the mihrab, at the spot which marks the beginning of Al-Hakam's 10th-century extension, is a monumental ribbed dome with ornate decoration. The mosque's architectural system of repeating two-tiered arches, with otherwise little surface decoration, is considered one of its most innovative characteristics and has been the subject of much commentary. The hall was large and flat, with timber ceilings held up by rows of two-tiered arches resting on columns. The building's original floor plan follows the overall form of some of the earliest mosques https://www.velwinscasino.gr/ built from the very beginning of Islam.

Being surrounded by Muslim architecture and peering into a church, all within the same building, is quite a peculiar experience. After the Christians reconquered Spain, the mosque was deemed too beautiful to destroy. Those were recycled by the Moors as they began work on the mosque.

In the courtyard, there are citrus trees and palms planted in rows mimicking the columns found inside the mosque. The arches are doubled, which at the time was a new building innovation, allowing for higher ceilings to be built. The columns of the mosque support the famous alternating red and white brick arches which are said to be inspired by the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. The King immediately converted the mosque into a Catholic cathedral, though the actual building was left intact. The hall’s eleven naves were comprised of two-tiered columns, made of jasper, marble and granite, which support the carved wooden-beam ceiling, a design which is known as hypostyle.

This tension between architectural languages remains one of the most debated aspects of the Mosque-Cathedral. Where the mosque emphasizes lateral expansion and spatial fluidity, the nave asserts axial hierarchy and vertical dominance. The cathedral nave, by comparison, disrupts this subdued ambiance, channeling light to highlight Christian iconography, thus shifting the experiential narrative. Narrow clerestory windows filter sunlight through layered arches, producing a dim, almost mystical interior. Perhaps the most contentious intervention came in the 16th century when Charles V authorized the construction of a cruciform nave at the heart of the hypostyle hall. While its structural framework remained largely intact, successive modifications introduced Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque elements, fundamentally altering the building’s original spatial and symbolic intent.

Choir stalls

Early alterations to the building were limited, with the cathedral’s first altar being installed below one of the skylights that was added to the building as part of Hakam II’s extension. Under Abd Al-Rahman II, eight new naves were added to the south side of the hall, with new Moorish-made columns being erected next to the already existing Roman and Visigoth ones. Cordoba’s growing population meant that an extension of the prayer hall became necessary. The need to call the faithful to prayer led to the construction of a minaret by Hisham I, who came to power upon the death of his father, Abd Al-Rahman I, in 788. This is the wall in a mosque which faces towards Mecca, although in this case, for reasons unknown, it actually faces south, rather than towards the holy city which is located to the south-east of Córdoba. The area inside is made up of a forest of columns with a harmonious colour scheme of red and white arches.

A design by Hernán Ruiz III (son of Hernán Ruiz II) was chosen, encasing the original minaret structure into a new Renaissance-style bell tower. The most significant alteration of all, however, was the building of a Renaissance cathedral nave and transept – forming a new Capilla Mayor es – in the middle of the expansive mosque structure, starting in 1523. In the late 15th century a more significant modification was carried out to the Villaviciosa Chapel, where a new nave in Gothic style was created by clearing some of the mosque arches on the east side of the chapel and adding Gothic arches and vaulting. The first precisely dated chapel known to be built along the west wall is the Chapel of San Felipe and Santiago, in 1258.